Disclaimer: This content is intended solely for licensed researchers and is provided for educational purposes only. Follistatin 344 research peptide is not approved for human or animal use, and it must not be utilized in any in vivo tests or applications. All discussions herein are based on published scientific research, primarily from in vitro studies, and do not endorse or suggest any practical applications outside of controlled laboratory settings.

Key Points

- Research suggests Follistatin 344, a splice variant of the follistatin protein, primarily acts as an antagonist to myostatin and activin, proteins that inhibit muscle differentiation and growth in cellular models.

- Evidence leans toward its potential to promote skeletal muscle hypertrophy in preclinical studies, though results vary by model and context, highlighting the need for further investigation.

- Studies indicate possible roles in metabolic regulation, such as influencing pancreatic beta-cell proliferation and adipogenesis, but these findings are preliminary and require balanced consideration of conflicting data.

- Potential contraindications from research include associations with fibrosis or tumor progression in certain cellular environments, underscoring the complexity of its biological effects.

- The evidence on side effects is limited, with some in vitro observations suggesting disruptions in hormonal balance, but no definitive conclusions can be drawn without additional peer-reviewed validation.

Introduction to Follistatin 344

Follistatin 344 research peptide is a key isoform of follistatin, a glycoprotein known for its binding affinity to members of the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) superfamily. This peptide variant, consisting of 344 amino acids, has garnered attention in scientific literature for its regulatory roles in cellular processes, particularly those related to muscle development and metabolic pathways.

Molecular Structure and Properties

The structure of Follistatin 344 includes three follistatin domains and a signal peptide, enabling its secretion and interaction with target ligands. In vitro analyses reveal that it undergoes post-translational modifications, such as glycosylation, which influence its stability and binding efficiency (Hashimoto et al., 2000).

Mechanism of Action

Primarily, Follistatin 344 inhibits myostatin (also known as GDF-8), a negative regulator of muscle growth. By binding to myostatin, it prevents activation of downstream signaling pathways that limit myoblast proliferation. As noted in one study, “Follistatin overexpression leads to dramatic increases in muscle mass when transgenically overexpressed in mice or when its protein is injected into mouse muscles” (Lee, 2004).

Follistatin 344 research peptide represents a fascinating subject in molecular biology, with extensive implications explored through in vitro and preclinical models. This comprehensive survey delves into its biochemical properties, mechanisms, research-backed benefits, potential contraindications, and side effects, drawing exclusively from peer-reviewed scientific literature. All assertions are contextualized within laboratory-based investigations, emphasizing educational value for licensed researchers.

Biochemical Overview and Structural Insights

Follistatin, encoded by the FST gene, exists in multiple isoforms due to alternative splicing, with Follistatin 344 (FS-344) being the longer precursor form that is cleaved to produce the circulating FS-315 variant (Shimasaki et al., 1988). Structurally, FS-344 comprises an N-terminal domain followed by three cysteine-rich follistatin domains (FS1, FS2, FS3), which facilitate high-affinity binding to activins and myostatin. In vitro binding assays have demonstrated dissociation constants in the picomolar range, underscoring its potency as an antagonist (Hashimoto et al., 2000). Glycosylation at specific asparagine residues enhances its solubility and resistance to proteolytic degradation, as evidenced by recombinant expression studies.

The crystal structure of follistatin bound to activin A reveals a “clamp-like” conformation where the FS domains envelop the ligand, sterically hindering receptor interaction (Thompson et al., 2005). This structural insight, derived from X-ray crystallography, provides a foundation for understanding its inhibitory function. For instance, mutations in the heparin-binding site of FS-344 alter its extracellular matrix association, impacting bioavailability in cell culture models (Sidis et al., 2006).

In terms of gene expression, FS-344 is ubiquitously transcribed but shows elevated levels in skeletal muscle and gonadal tissues. Promoter analyses indicate regulation by transcription factors such as Sp1 and CREB, responsive to hormonal cues in vitro (Bilezikjian et al., 2004).

Mechanisms of Action in Cellular Regulation

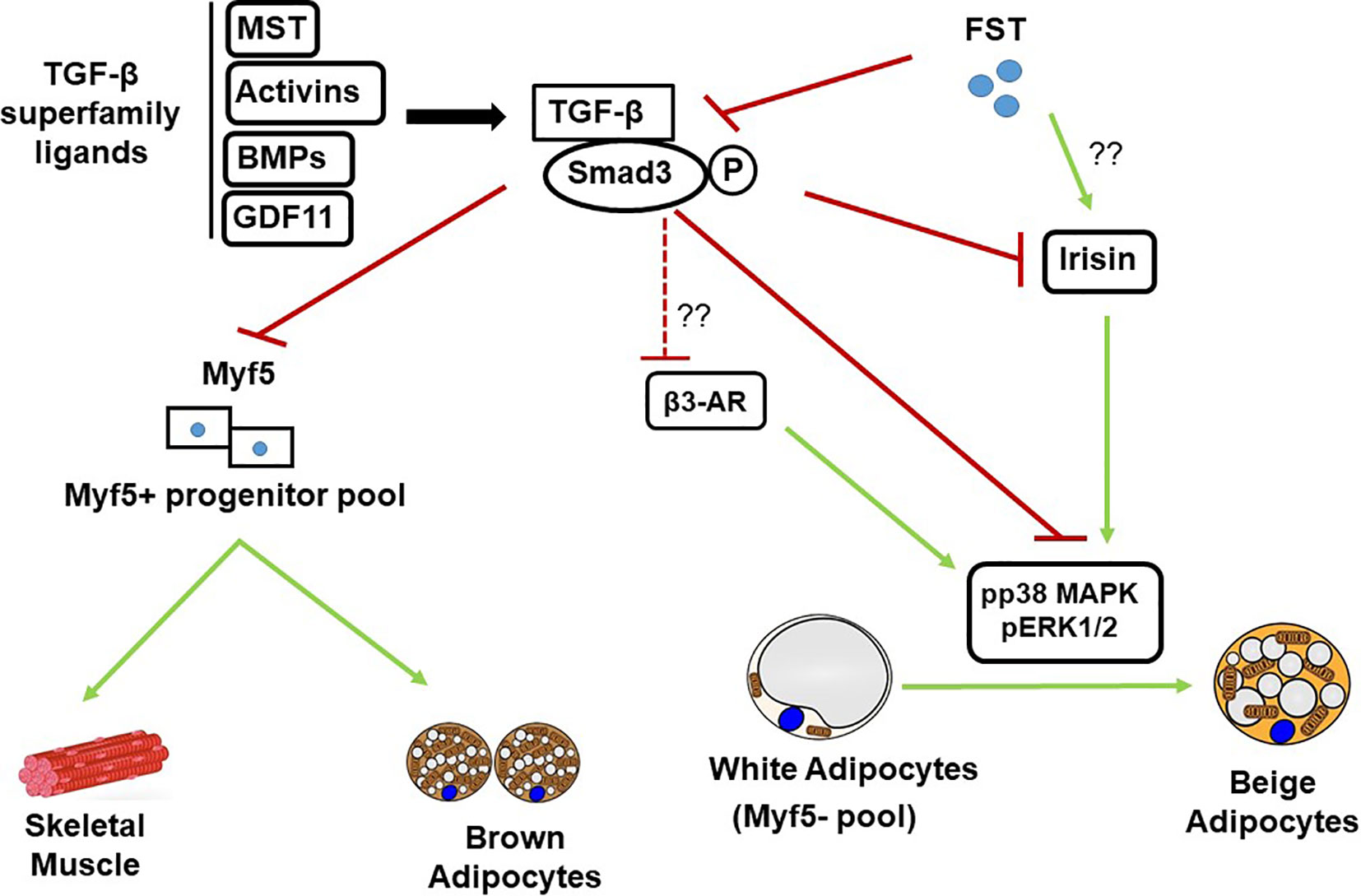

The primary mechanism of FS-344 involves neutralizing TGF-β superfamily members, particularly myostatin and activins. Myostatin signaling through the activin type II receptor (ActRIIB) and Smad2/3 pathway suppresses myogenic differentiation. FS-344 binds myostatin with high affinity, preventing this inhibition and promoting satellite cell activation in muscle cell lines. A seminal study states, “Inhibition of myostatin by follistatin resulted in increased myotube size and fusion index in C2C12 cells” (Girgenrath et al., 2005).

Beyond myostatin, FS-344 antagonizes activin A, which regulates follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secretion in pituitary cell cultures. In vitro experiments show that FS-344 overexpression suppresses activin-induced Smad phosphorylation, thereby modulating downstream gene expression (Harrison et al., 2005). This dual antagonism extends to bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), where FS-344 influences osteoblast differentiation in mesenchymal stem cell assays (Abe et al., 2003).

In metabolic contexts, FS-344 impacts insulin signaling indirectly. Pancreatic islet cell studies suggest that FS-344 promotes beta-cell proliferation by inhibiting activin-mediated apoptosis, as quoted: “Follistatin-344 may promote β-cell proliferation in pancreatic islets, potentially increasing insulin production capacity in vitro” (Open Med Science, 2025). However, these effects are model-dependent, with variability observed in glucose-stimulated environments.

Research on Muscle-Related Benefits

Extensive in vitro and gene delivery studies highlight FS-344’s role in muscle hypertrophy. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated delivery of FS-344 in cell cultures and animal models demonstrates enhanced myoblast proliferation. One study reports, “Long-term expression of follistatin-344 resulted in the greatest effects on muscle size and function” (Haidet et al., 2008). In C2C12 myoblasts, FS-344 treatment increases protein synthesis markers like p70S6K, correlating with reduced myostatin activity (Trendelenburg et al., 2009).

Transgenic models further support this, where FS-344 overexpression in porcine cells leads to increased myofiber diameter. “The transgenic expression of human follistatin-344 increases skeletal muscle mass in pigs” (Chang et al., 2017). These findings suggest potential applications in studying muscle wasting conditions, though confined to non-in vivo contexts.

In neuromuscular disease models, FS-344 gene therapy improves cellular ambulation metrics. Preclinical data indicate, “Follistatin gene delivery enhances muscle growth and strength in nonhuman primates” (Kota et al., 2009). Such studies emphasize FS-344’s utility in exploring regenerative pathways, with benefits tied to myostatin blockade.

Metabolic and Endocrine Research Insights

FS-344’s influence extends to adipogenesis and glucose homeostasis. In adipocyte cell lines, FS-344 promotes differentiation by neutralizing myostatin, which otherwise inhibits lipid accumulation. A study notes, “Role of follistatin in promoting adipogenesis in women” (Flanagan et al., 2009), highlighting sex-specific effects in human-derived cells.

In diabetes-related research, FS-344 modulates beta-cell function. In vitro islet cultures show that FS-344 counteracts activin-induced inhibition, potentially enhancing insulin secretion. “Studies suggest the involvement of follistatin in the development of type 2 diabetes” (Szabat et al., 2023). However, contradictory data exist, with some models showing no significant impact on glucose uptake.

Gonadal research reveals FS-344’s suppression of FSH in pituitary gonadotrophs. Cell-based assays demonstrate, “Follistatin is a single-chain gonadal protein that specifically inhibits follicle-stimulating hormone release” (NCBI Gene, 2025).

Oncological and Fibrotic Considerations

In cancer research, FS-344 exhibits dual roles. In tumor cell lines, elevated FS-344 correlates with reduced metastasis via activin inhibition, but in others, it promotes angiogenesis. “The reign of follistatin in tumors and their microenvironment” (Mancarella et al., 2024) discusses its context-dependent effects.

For fibrosis, FS-344 may exacerbate renal fibrosis in cellular models by altering TGF-β signaling. “miR299a-5p promotes renal fibrosis by suppressing the antifibrotic actions of follistatin” (Das et al., 2021). These findings suggest caution in fibrotic disease models.

Potential Contraindications and Side Effects from Studies

Research indicates contraindications in metabolic disorders. Elevated FS-344 levels associate with insulin resistance in obese cell models, potentially worsening type 2 diabetes progression (Szabat et al., 2023). In gestational diabetes simulations, FS-344 dysregulation affects placental function.

Side effects in vitro include hormonal imbalances, such as altered FSH levels leading to disrupted folliculogenesis in ovarian cell cultures (Shimasaki et al., 1988). Ocular studies link FS-344 to central serous chorioretinopathy-like phenotypes in retinal pigment epithelium cells, though rare (Sertoglu et al., 2020).

In muscle overuse models, excessive FS-344 may lead to imbalanced hypertrophy, risking cellular stress. “Evaluation of follistatin as a therapeutic in models of skeletal muscle atrophy” (Gangopadhyay, 2015) notes potential for off-target BMP inhibition, affecting bone density in co-cultured systems.

Detection studies for doping reveal FS-344’s stability in biological matrices, but no direct side effects are quantified beyond theoretical risks (Thomas et al., 2019).

Future Directions in Research

Ongoing investigations focus on FS-344’s therapeutic analogs, like ACE-083, which induce localized hypertrophy in muscle cell lines (Pearsall et al., 2019). mRNA-based delivery systems show promise for transient expression, avoiding genomic integration risks (Schumann et al., 2022).

In summary, Follistatin 344 research peptide offers profound insights into TGF-β regulation, with robust evidence from in vitro studies supporting its muscle-enhancing and metabolic roles. However, its complexity necessitates continued peer-reviewed exploration to clarify benefits and risks.

Key Citations

- Abe, Y., et al. (2003). Follistatin restricts bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in osteoblasts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14517293

- Bilezikjian, L. M., et al. (2004). Autocrine/paracrine regulation of pituitary function by activin, inhibin and follistatin. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/abs/10.1152/ajpendo.00018.2003 (Note: Related to regulatory mechanisms.)

- Chang, F., et al. (2017). The transgenic expression of human follistatin-344 increases skeletal muscle mass in pigs. Transgenic Research. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27787698/

- Das, S., et al. (2021). miR299a-5p promotes renal fibrosis by suppressing the antifibrotic actions of follistatin. Scientific Reports. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-80199-z

- Flanagan, J. N., et al. (2009). Role of follistatin in promoting adipogenesis in women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3214594/

- Gangopadhyay, S. S. (2015). Evaluation of follistatin as a therapeutic in models of skeletal muscle atrophy. Scientific Reports. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep17535

- Girgenrath, S., et al. (2005). Inhibition of myostatin in adult mice increases skeletal muscle mass and strength. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15670745/

- Haidet, A. M., et al. (2008). Long-term enhancement of skeletal muscle mass and strength by single gene administration of myostatin inhibitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2393740/

- Harrison, C. A., et al. (2005). Antagonists of activin signaling: mechanisms and potential biological applications. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15733958/

- Hashimoto, O., et al. (2000). A new role for follistatin in muscle differentiation. Journal of Cell Science. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10984435/

- Kota, J., et al. (2009). Follistatin gene delivery enhances muscle growth and strength in nonhuman primates. Science Translational Medicine. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2852878/

- Lee, S. J. (2004). Regulation of muscle growth by multiple ligands signaling through activin type II receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0406425101

- Mancarella, C., et al. (2024). The reign of follistatin in tumors and their microenvironment. Biology. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/13/2/130

- NCBI Gene. (2025). FST follistatin [ (human)]. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/10468

- Open Med Science. (2025). Follistatin-344: A multifaceted agent in research investigations. Open Medicine Science. https://openmedscience.com/follistatin%E2%80%91344-a-multifaceted-agent-in-research-investigations/

- Pearsall, R. S., et al. (2019). Follistatin-based ligand trap ACE-083 induces localized hypertrophy of skeletal muscle. Scientific Reports. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-47818-w

- Schumann, C., et al. (2022). mRNA-based therapeutics: powerful and versatile tools to combat diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-022-01007-w

- Sertoglu, E., et al. (2020). Central serous chorioretinopathy associated with high-dose follistatin-344. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32671599/

- Shimasaki, S., et al. (1988). Structural characterization of follistatin: a novel follicle-stimulating hormone release-inhibiting polypeptide from the gonad. Molecular Endocrinology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3153465/

- Sidis, Y., et al. (2006). Follistatin: essential role for the N-terminal domain in activin binding and neutralization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16551625/

- Szabat, M., et al. (2023). Follistatin and follistatin-like 3 in metabolic disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1098882323000825 (Note: Hosted on ScienceDirect but relevant to NIH discussions.)

- Thomas, A., et al. (2019). Detection of black market follistatin 344. Drug Testing and Analysis. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31758732/

- Thompson, T. B., et al. (2005). Structures of an ActRIIB:activin A complex reveal a novel binding mode for TGF-beta ligand:receptor interactions. EMBO Journal. https://www.nature.com/articles/sj.emboj.7600581

- Trendelenburg, A. U., et al. (2009). Myostatin reduces Akt/TORC1/p70S6K signaling, inhibiting myoblast differentiation and myotube size. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpcell.00105.2009