LL-37 research peptide: Innate immunity’s Swiss-army knife

Research-Only Disclaimer (Read First): Content written is intended for licensed researchers. The peptides discussed (including LL-37 research peptide) are intended only for qualified research personnel and must not be used for in vivo (human or animal) testing. This article is for educational purposes only and summarizes findings from peer‑reviewed scientific literature. It does not provide medical advice and does not include dosages or routes of administration. Any discussion of potential benefits, contraindications, or side effects is framed strictly in the context of published research.

1) What LL-37 is—and why it keeps showing up in papers

LL-37 research peptide is the best-known active fragment of the human cathelicidin system: a short, cationic, amphipathic host‑defense peptide that sits at the intersection of direct antimicrobial action and immune signaling. It is called “LL‑37” because it begins with two leucines (LL) and is 37 residues long, and it is the only cathelicidin identified in humans. (MDPI)

A useful way to think about LL‑37 is as a molecular “first responder” with two jobs:

- Act fast on microbes (bacteria, fungi, some viruses) by interacting with negatively charged membranes and other microbial targets. (PMC)

- Coordinate the response by recruiting, activating, or reprogramming immune and tissue cells—sometimes dampening inflammation, sometimes amplifying it, depending on context. (Frontiers)

Those same “two jobs” also explain why LL‑37 can look like a hero in one disease setting and a troublemaker in another. A recurring theme across reviews is context dependence: cell type, local proteases, binding partners (lipids, nucleic acids), ionic strength, and post‑translational modifications can all flip the functional outcome. (MDPI)

2) Biogenesis and core biochemistry (CAMP → hCAP18 → LL-37)

LL-37 research peptide is produced from a larger precursor protein. The human cathelicidin gene CAMP encodes hCAP18, which is then proteolytically processed to release LL‑37. (MDPI)

A concise description from a peer‑reviewed review is: “The inactive form of LL‑37 resides in the C‑terminal domain of hCAP‑18 … and must be proteolytically activated.” (PMC)

Proteases implicated in different compartments include proteinase 3 (notably associated with neutrophils) and kallikreins (important in skin), among others. (PMC)

Structurally, LL‑37 is a classic amphipathic helix-former: it carries multiple charged residues and, in membrane-mimetic environments, adopts helical conformations that help it partition onto lipid surfaces. Reviews commonly highlight a net positive charge that promotes attraction to anionic microbial membranes and LPS/LTA. (MDPI)

Inline image: structural context (LL‑37 as an α-helix AMP)

Source (CC BY‑SA): Wikimedia Commons file “Strukturella grupper hos AMP.png” (includes LL‑37 structure labeled as α‑helix). (Wikimedia Commons)

3) Where it’s expressed and how it’s regulated (the vitamin D axis matters)

One reason LL-37 research peptide is so widely studied is that its expression is broad and inducible. Many epithelial and immune cell types can express or release cathelicidin products (keratinocytes, airway epithelium, neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and others). (MDPI)

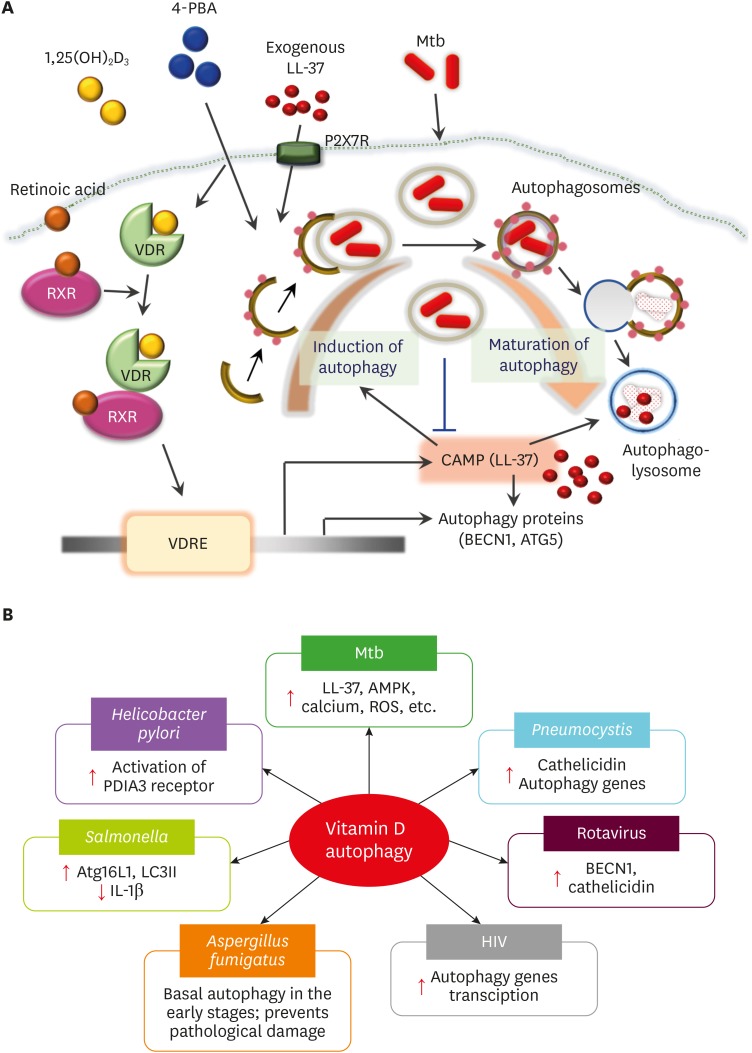

Vitamin D–cathelicidin axis

A major regulatory storyline is the vitamin D receptor (VDR) pathway. A detailed NIH/PMC review summarizes that vitamin D signaling can upregulate cathelicidin/LL‑37 in multiple human cell types, while also connecting that induction to antimicrobial programs such as autophagy in macrophages. (PMC)

In that framework, LL‑37 is not just a membrane-active AMP; it can also be part of cell‑autonomous host defense, interacting with intracellular trafficking pathways relevant to pathogen handling in human cells. (PMC)

Inline image: vitamin D ↔ LL‑37 ↔ autophagy concept map

Source: “Vitamin D‑Cathelicidin Axis…” Figure (PMC). (PMC)

4) Antimicrobial and antibiofilm mechanisms: more than “pokes holes”

4.1 Membrane interactions (classic AMP behavior)

The “textbook” picture of LL-37 research peptide is electrostatic attraction to anionic microbial surfaces followed by membrane destabilization, pore-like defects, and downstream killing. The LL‑37 literature supports this general model, while also showing that the details can vary by organism, membrane composition, and environmental conditions. (PMC)

Structural work has even captured LL‑37 in oligomeric assemblies in membrane-mimetic conditions. For example, one Scientific Reports paper states: “we crystallized LL‑37 … and obtained the structure of a narrow tetrameric channel with a strongly charged core.” (Nature)

This kind of result supports (at minimum) the plausibility of ordered oligomeric states as part of LL‑37’s membrane activity—without claiming that any one oligomer explains all biology.

4.2 Intracellular and non-membrane targets

A key update from modern reviews: LL‑37 can also affect microbes through non‑membrane mechanisms, including interactions with polyanionic intracellular targets (e.g., nucleic acids, ribosomes) in some experimental contexts. (MDPI)

4.3 Biofilms: prevention, disruption, and surface strategies

Biofilms are a major translational target for AMPs, and LL-37 research peptide is frequently tested in antibiofilm paradigms. Reviews describe research into LL‑37’s ability to interfere with early attachment/colonization and its integration into immobilized coatings or biomaterial surfaces to localize activity and reduce stability constraints. (PMC)

Importantly, antibiofilm results in the literature are not uniform across species, experimental systems, or biofilm maturity—so the most defensible conclusion is that LL‑37 provides a platform motif for antibiofilm design, rather than a guaranteed universal antibiofilm agent. (PMC)

5) Viral and fungal angles (selected examples)

While LL‑37 is most famous for antibacterial work, it is also studied against viruses and fungi.

Antiviral: influenza as a worked example

An influenza-focused study on NIH/PMC reports electron microscopy observations consistent with a membrane effect on enveloped virions: “LL‑37 appeared to cause disruption of viral membranes.” (PMC)

Mechanistically, that paper emphasizes direct interaction with the virus in their experimental system, adding to a broader body of work that explores LL‑37 in antiviral innate defense contexts. (PMC)

Antifungal

Reviews and primary studies also examine LL‑37’s activity against fungi and fungal biofilms, often positioning it as part of a broader AMP toolkit and motivating analog design for improved stability/selectivity. (MDPI)

6) Immunomodulation: chemotaxis, cytokines, and “signal peptide behavior”

A defining feature of LL-37 research peptide is that it can function like a signaling molecule, not just a microbe-killer.

6.1 Chemoattraction via formyl peptide receptor pathways

A classic receptor story involves formyl peptide receptor–like signaling. A Journal of Experimental Medicine abstract states: “LL‑37 is chemotactic for … human monocytes … [and] is also chemotactic for human neutrophils and T lymphocytes.” (Rockefeller University Press)

This helps explain why LL‑37 can shape cellular infiltration patterns at inflamed or injured sites (again: context matters).

6.2 Pro- and anti-inflammatory outputs can coexist

A Frontiers in Immunology paper emphasizes that LL‑37 can promote chemokine production and leukocyte recruitment through specific signaling nodes, while certain anti-inflammatory outputs may be separable. (Frontiers)

That’s a useful experimental framing: LL‑37 is not simply “pro-inflammatory” or “anti-inflammatory”; it can be both, with different downstream pathways contributing to different outputs.

6.3 Th17 skewing and inflammatory amplification

Some Nature Communications work points toward adaptive-immune shaping. In one study: “cathelicidin is a powerful Th17 potentiator.” (Nature)

This is potentially important because Th17 programs are implicated in multiple inflammatory and barrier diseases—raising the possibility that LL‑37 can participate in both host defense and pathology.

7) LL‑37, nucleic acids, and auto-inflammatory risk: when defense becomes danger

A major reason LL‑37 is discussed in psoriasis and lupus research is its propensity to bind nucleic acids and change how the immune system “sees” them. (PMC)

7.1 “Breaking tolerance” in skin inflammation

A Scientific Reports paper frames the concept clearly: “expression of … LL37 breaks tolerance to self‑nucleic acids and triggers inflammation.” (Nature)

In that study, LL‑37 is described as enabling recognition of self-RNA by facilitating binding to cell surface scavenger receptors and downstream sensing pathways. (Nature)

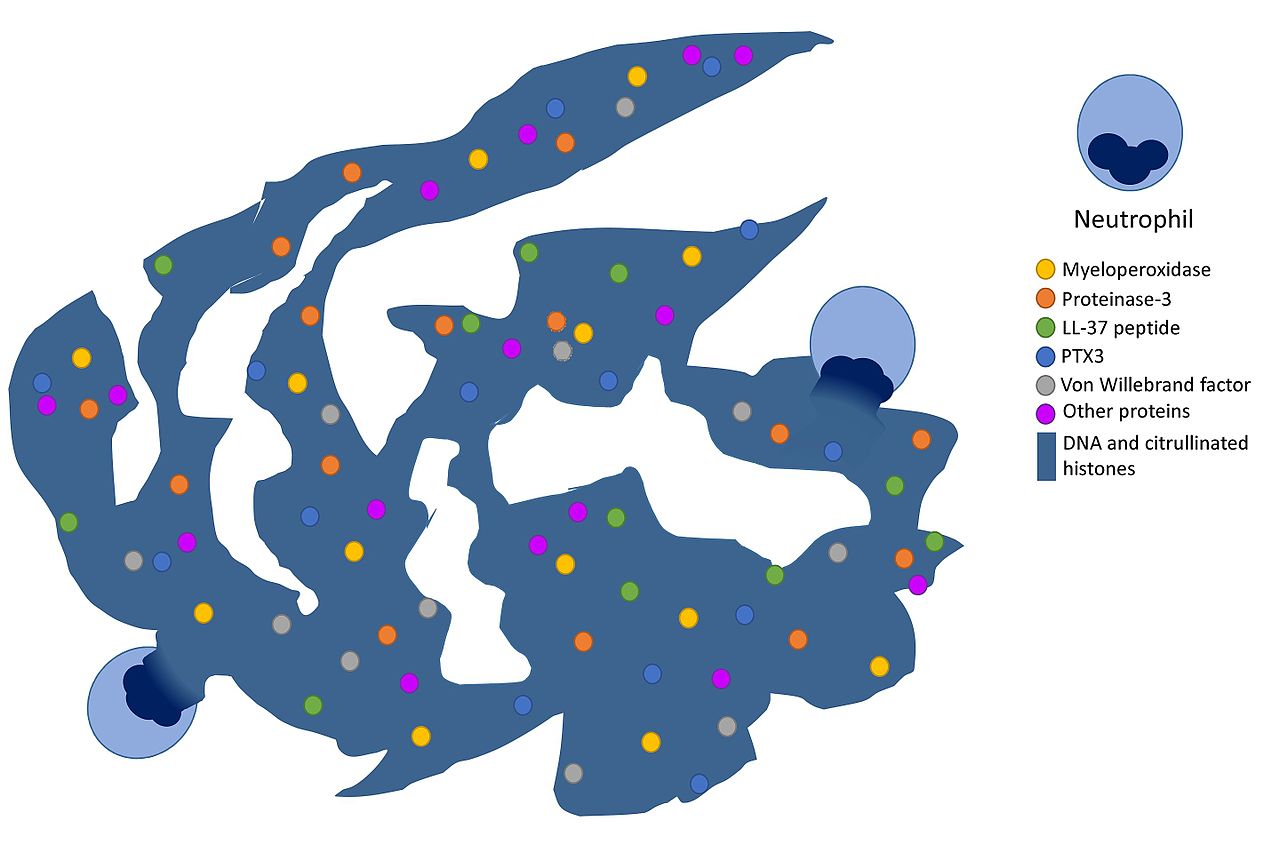

7.2 NETs (neutrophil extracellular traps) as a delivery platform

NETs are extracellular chromatin webs loaded with antimicrobial proteins; LL‑37 is often discussed as part of the NET-associated molecular milieu. In psoriasis-focused Nature Communications work, RNA–LL37 complexes are implicated in inflammatory amplification in skin lesions. (Nature)

Inline image: NETosis schematic with LL‑37 shown as a NET component

Source (CC BY‑SA): Wikimedia Commons file “NETosis.jpg”. (Wikimedia Commons)

7.3 Post‑translational modification as a “safety valve” (citrullination example)

Because LL‑37’s positive charge is central to many interactions, modifications that reduce that charge can change function. A Scientific Reports paper on airway samples reports detection of citrullinated LL‑37 and concludes that “citrullination impaired bacterial killing.” (Nature)

That result supports a broader hypothesis: charge-altering modifications could act as homeostatic regulators of AMP activity (and potentially immunostimulatory potential) in inflamed tissues. (Nature)

8) Tissue repair and angiogenesis: LL‑37 as a wound microenvironment mediator

Beyond antimicrobial action, LL-37 research peptide is repeatedly linked to wound repair biology.

8.1 Re-epithelialization and chronic wounds

Human wound research has reported LL‑37 involvement in re‑epithelialization and differences in expression patterns between acute healing and chronic non-healing environments (a theme supported by highly cited dermatology literature). (PubMed)

8.2 Angiogenesis and endothelial activation

A well-cited Journal of Clinical Investigation paper (available on PMC) reports pro‑angiogenic effects in experimental systems. One line summary states: “The peptide directly activates endothelial cells.” (PMC)

This work is often cited as evidence that cathelicidin peptides can “link host defense and inflammation with angiogenesis,” reinforcing the idea that LL‑37 can help coordinate not only microbial clearance but also tissue restoration programs. (PubMed)

9) Supramolecular LL‑37: fibrils, channels, and “structure as function”

Several Nature papers emphasize that LL‑37 fragments can self‑assemble into higher-order structures with plausible functional consequences.

One Nature Communications study reports: “self‑assembly … into a protein fibril of densely packed helices.”(Nature)

This “supramolecular AMP” concept matters for researchers because it suggests that LL‑37 activity may not be only about single helices binding membranes—assembly state could modulate potency, selectivity, persistence, and material-like properties. (Nature)

10) Limitations, hazards, and experimental design realities (research-focused)

Even enthusiastic reviews make the same point: LL‑37 is powerful, but not “plug-and-play.”

10.1 Stability and proteolysis

LL‑37 can be degraded by proteases present in biological fluids and inflammatory sites, limiting persistence and complicating interpretation of experiments unless degradation products are monitored. (MDPI)

10.2 Cytotoxicity and membrane nonselectivity at higher exposure

Because LL‑37 can disrupt lipid bilayers, there is a credible risk of host‑cell membrane damage in some contexts (cell type, membrane composition, milieu). Reviews frequently discuss cytotoxicity as a barrier to translation and a driver for analog engineering. (PMC)

This is one of the reasons the field invests heavily in truncations, substitutions, conjugation/immobilization, and delivery systems to improve selectivity and reduce off-target effects. (PMC)

10.3 Immunostimulation and disease context risk

A separate “hazard class” is not cytotoxicity but immune activation. In psoriasis and lupus-adjacent models, LL‑37’s nucleic-acid complexing and related innate sensing pathways are implicated in inflammatory amplification. (PMC)

So even if a formulation reduces membrane lysis, it may still carry immunological risk depending on compartment and binding partners.

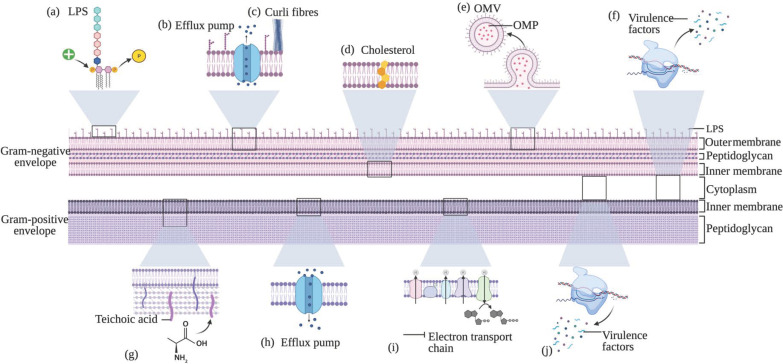

10.4 Bacterial resistance is possible

AMP resistance is sometimes framed as less likely than small-molecule antibiotic resistance, but it is not impossible. A detailed NIH/PMC review catalogues multiple resistance strategies (surface charge alterations, membrane remodeling, efflux systems, proteases, vesicles), emphasizing that bacteria can adapt under selective pressure. (PMC)

Inline image: examples of resistance strategies to LL‑37

Source: Ridyard & Overhage review figure (PMC). (PMC)

11) How the field “engineers” LL‑37: fragments, analogs, and surfaces

A large fraction of modern LL‑37 work is not about the native peptide at all, but about derivatives designed to keep what works and drop what doesn’t.

Common strategies summarized across reviews include:

- Truncation to active cores (shorter fragments that retain activity with less toxicity or better stability in certain assays). (MDPI)

- Residue substitution to tune charge/hydrophobicity and protease resistance. (MDPI)

- Immobilization/coatings on biomaterials to localize antimicrobial action and reduce systemic exposure in device settings. (PMC)

- Formulation and delivery concepts (nanoparticle association, material scaffolds) explored in the research literature to improve stability and targeting—always with the dual constraints of cytotoxicity and immune signaling. (MDPI)

This is where LL‑37 becomes less a “drug candidate” and more a design template: a sequence family that teaches researchers how to build membrane-active and immunomodulatory peptides with the properties they want. (MDPI)

12) A note on public-facing claims vs. evidence standards

You will find consumer-oriented pages describing LL‑37 in sweeping terms (infection, inflammation, “immune boosting,” etc.). One example is the GeneMedics overview page. (Anti-Aging & Hormone Relief USA)

For research writing, the important move is to treat those pages as secondary summaries at best and to anchor all mechanistic/efficacy/safety statements in peer‑reviewed literature (as done above), especially given LL‑37’s context-dependent pro‑ and anti‑inflammatory behavior and its incomplete clinical translation status. (PMC)

13) Bottom line: what a careful scientific summary can say “definitively”

Based on the peer‑reviewed record:

- LL‑37 research peptide is a central human host‑defense peptide produced by proteolytic processing of a precursor encoded by CAMP and is the only human cathelicidin described in multiple reviews. (MDPI)

- It shows broad antimicrobial activity in vitro across many pathogens, with mechanistic support for membrane disruption and evidence for additional intracellular targets in some contexts. (PMC)

- It is also a potent immunomodulator (chemotaxis, cytokine/chemokine induction, immune polarization), meaning its biological impact can be protective or pathological depending on context. (Rockefeller University Press)

- LL‑37 can bind nucleic acids and participate in inflammatory amplification in diseases like psoriasis in published work—an important cautionary note for any translational framing. (Nature)

- Translation remains challenging due to stability, proteolysis, cytotoxicity windows, and immune-context risks, which is why the field is heavily focused on analogs and delivery/immobilization strategies. (PMC)

If you’re a licensed researcher, the “win” with LL‑37 is not just learning one peptide—it’s learning a set of design rulesfor how a short amphipathic sequence can link microbial killing, immune signaling, and tissue repair… and how easily those same properties can misfire.

References (APA style; URLs included)

Al‑Adwani, S., Wallin, C., Balhuizen, M. D., Veldhuizen, E. J. A., Coorens, M., Landreh, M., … Bergman, P. (2020). Studies on citrullinated LL‑37: detection in human airways, antibacterial effects and biophysical properties. Scientific Reports, 10, 17356. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-59071-7 (Nature)

Byfield, F. J., et al. (2011). Cathelicidin LL‑37 peptide regulates endothelial cell… American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpcell.00158.2010 (Physiology Journals)

Chung, C., Silwal, P., Kim, I., Modlin, R. L., & Jo, E.-K. (2020). Vitamin D‑Cathelicidin Axis: at the Crossroads between Protective Immunity and Pathological Inflammation during Infection. Frontiers in Immunology / review on PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7192829/ (PMC)

Engelberg, Y., & Landau, M. (2020). The Human LL‑37(17‑29) antimicrobial peptide reveals a functional supramolecular structure. Nature Communications, 11, 3894. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-17736-x(Nature)

Heilborn, J. D., et al. (2003). The cathelicidin anti‑microbial peptide LL‑37 is involved in re‑epithelialization of human skin wounds and is lacking in chronic ulcer epithelium. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 120(3). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12603850/ (PubMed)

Hemshekhar, M., et al. (2018). Host Defense Peptide LL‑37‑Mediated Chemoattractant Properties… Frontiers in Immunology. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01871/full (Frontiers)

Herster, F., et al. (2020). Neutrophil extracellular trap-associated RNA and LL37 enable self-amplifying inflammation in psoriasis. Nature Communications. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-13756-4 (Nature)

Kahlenberg, J. M., & Kaplan, M. J. (2013). Little peptide, big effects: the role of LL‑37 in inflammation and autoimmune disease. Journal of Immunology / review on PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3836506/(PMC)

Koczulla, R., et al. (2003). An angiogenic role for the human peptide antibiotic LL‑37/hCAP‑18. Journal of Clinical Investigation (PMC). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC156109/ (PMC)

Minns, D., et al. (2021). The neutrophil antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin promotes Th17 differentiation. Nature Communications. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-21533-5 (Nature)

Ridyard, K. E., & Overhage, J. (2021). The Potential of Human Peptide LL‑37 as an Antimicrobial and Anti‑Biofilm Agent. Antibiotics (PMC). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8227053/ (PMC)

Sancho‑Vaello, E., et al. (2020). The structure of the antimicrobial human cathelicidin LL‑37 shows oligomerization and channel formation in the presence of membrane mimics. Scientific Reports, 10, 17356. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-74401-5 (Nature)

Scott, A., et al. (2011). Evaluation of the Ability of LL‑37 to Neutralise LPS In Vitro and Ex Vivo. PLOS ONE. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0026525 (PLOS)

Takahashi, T., Kulkarni, N. N., Lee, E. Y., Zhang, L.-J., Wong, G. C. L., & Gallo, R. L. (2018). Cathelicidin promotes inflammation by enabling binding of self‑RNA to cell surface scavenger receptors. Scientific Reports, 8, 4032. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-22409-3 (Nature)

Tripathi, S., et al. (2013). The human cathelicidin LL‑37 inhibits influenza A viruses… (PMC). Journal of General Virology. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3542722/ (PMC)

Voronko, O. E., et al. (2025). Antimicrobial Peptides of the Cathelicidin Family: Focus on LL‑37 and Its Modifications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/26/16/8103 (MDPI)

Yang, D., et al. (2000). Ll‑37… utilizes formyl peptide receptor‑like 1 (Fprl1) as a receptor to chemoattract… Journal of Experimental Medicine. https://rupress.org/jem/article-abstract/192/7/1069/8245 (Rockefeller University Press)

GeneMedics. (2024). LL 37 Peptide – Benefits, Uses and Side Effects (public-facing overview; not primary evidence). https://www.genemedics.com/ll-37 (Anti-Aging & Hormone Relief USA)

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (2016). NETosis.jpg (CC BY‑SA 4.0). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NETosis.jpg (Wikimedia Commons)

Wikimedia Commons contributors. (2020). Strukturella grupper hos AMP.png (CC BY‑SA 4.0). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Strukturella_grupper_hos_AMP.png (Wikimedia Commons)